Inside the UK's

Poverty Panopticon

Black box algorithms and secretive AI tools sit at the heart of the UK's welfare system - with little accountability. Our investigation offers a glimpse into life inside the UK’s poverty panopticon.

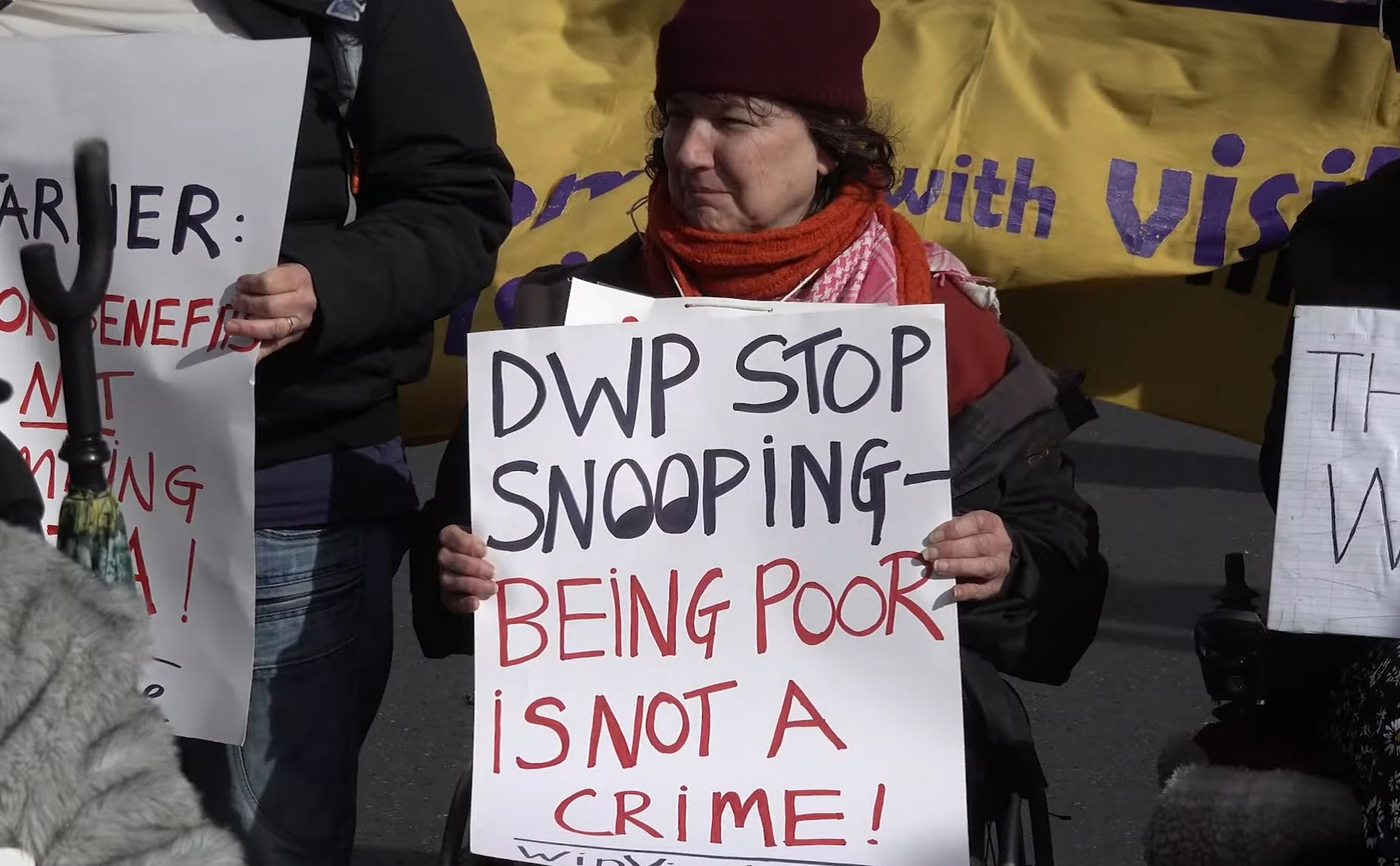

Millions of people in the UK are profiled, ranked and analysed by 'anti-fraud' algorithms every year as a condition of receiving welfare benefits.

Benefit 'fraud' crackdowns have been a favourite policy of governments of all stripes for decades. In the age of AI millions of people can be treated with suspicion simultaneously, and a machine can brand whole groups of people a fraud risk at the click of a button.

AI is a growing part of our welfare system.

Machines aren't yet judge, jury and executioner in the UK's welfare system. Decisions about who receives state support and who is a fraud risk are still not wholly automated - but the role of artificial intelligence is growing.

The previous government even sought to bring in a law to demand banks constantly monitor the accounts of welfare recipients and potentially anyone linked to them.

With over 170,000 petitioners and 40+ human rights groups and organisations, we robustly resisted these powers in public & in Parliament. We defeated the Orwellian plans and got the Data Bill dropped ahead of the general election - but we must all be vigilant to stop it coming back.

Every government agency claims its algorithms are no threat to data rights and have a low risk of bias - even those which use protected traits like gender and age in their models. Being flagged by these automated tools is more than a hiccup, it can lead to intrusive document demands or delays to payments, so even a low risk could have devastating results.

We have been investigating the digital welfare state and its automated fraud & error tools for years – uncovering how millions of people are profiled to produce risk scores that claim to predict how they will behave. Transparency is limited, and freedom of information battles to obtain details have been fraught. Despite the secrecy, it is clear that risky data processing, profiling and AI are at the heart of the welfare state's digital suspicion machine.

There are still a lot of unknowns, including details of the black box anti-fraud tool in Universal Credit that the DWP is fighting to keep secret. But, through the work of Big Brother Watch and others, we can glimpse inside the UK’s poverty panopticon.

RISK-BASED VERIFICATION

One of the oldest tools and for a time the most common, used to profile welfare applicants, is Risk-Based Verification (RBV).

At one time, 1 in 3 local councils used RBV to risk-assess claims for Housing Benefit and Council Tax Support.

Risk assessments are done using software bought from private companies, including the credit reference agency TransUnion and the data science firm Xantura.

RBV pulls together a huge amount of information from benefits applications and runs it through a secret model that analyses how much an application looks like previous fraudulent claims.

If you share traits with fraudsters, you'll get branded as high-risk - even if you've done nothing wrong.

Some of the factors in Xantura's model:

- Your home's council tax band

- Number of children

- Do you have a partner?

- Gender

- Age

- Postcode profiles

- How much sick pay have you received?

- Have you claimed before?

Some of these factors are proxies for protected characteristics - like your postcode, which could be linked to your

ethnic background. These postcode profiles were drawn up by the Office for National Statistics.

Ethnicity Central

- High representation of non-white ethnic groups

- High number of young adults

- Above-average divorce rates

- Renter in flats

- Commute on public transport

The factors are given secret weightings, decided by the software supplier, and added up to calculate your fraud risk score. You'll never be told your score.

Multicultural Metropolitan

- Lots of families with school-age children

- Diverse ethnic mix, with fewer UK-born residents

- Renters in terraced houses

- Above average unemployment

Councils claim that the model is unbiased, but snippets of the profiles linked to different risk scores show that certain groups of people are more likely to end up in certain categories.

Hard-Pressed Living

- Above rates of divorce & separation

- Live in socially rented homes

- Lower proportion of higher-level qualifications

- Above-average white ethnic background

What do these risk scores mean?

Risk scores decide how much evidence you'll have to give to the council to access benefits. The higher your risk score, the more invasive the evidence demands.

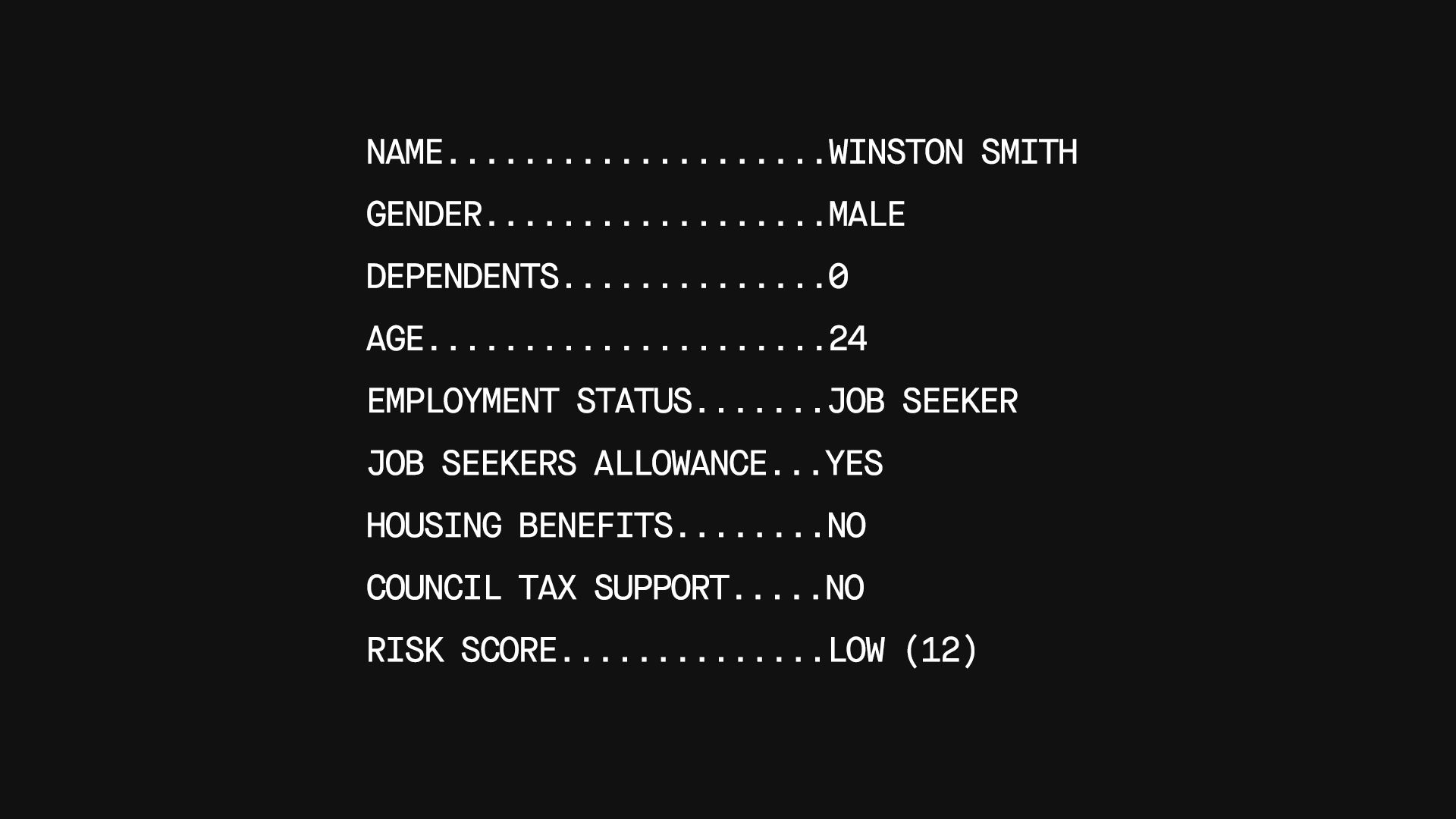

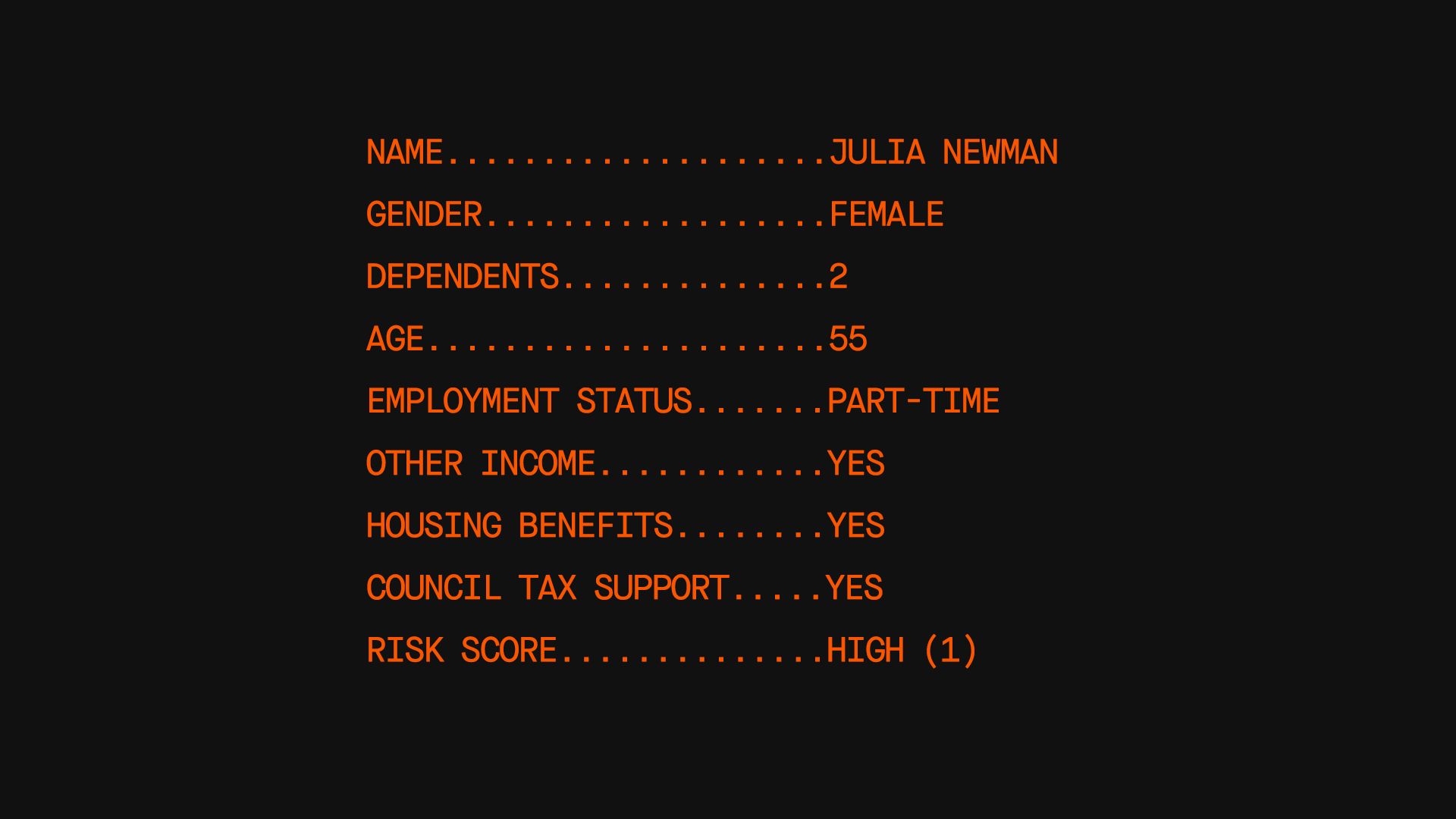

Xantura provided some risk profiles to councils, we obtained them via FOI.

Why do they matter?

Risk scores decide how much evidence you have to provide to the council to get your benefits. The higher the risk score, the more invasive the evidence.

Low risk scores means officials might only ask to see copies of documents, while higher risk scores will see the council demand originals and could even lead to follow-up calls and home visits.

RISK SCORE - LOW

More likely to be single men aged under 25, non-working and with low capital.

Most receive job seekers allowance, income support or Employment and Support Allowance. Council Tax Band A, likely to be housing association or privately rented.

RISK SCORE - MEDIUM

Typically couples 45-64, with children aged up to 10, with a bias to Council Tax band C

Above average proportion have over £6,000 in savings. Mostly ‘standard’ cases claiming HB/CTB [Housing Benefit/Council Tax Benefit].”

RISK SCORE - HIGH

Typically couples between ages 35-54. Many are not working or work part-time with some ‘other’ income.

Generally standard cases claiming either Council Tax Benefits or Housing Benefits, with bias to having a previous claim.

Council officers cannot lower your score if it looks wrong, but they can raise it in some circumstances.

If the machine suspects you, officials will too.

TransUnion even keeps a “national claimant register” to cross-reference the risk checks from different councils – meaning by making just one application you could be on a private company’s database for years.

Our investigation found that many councils do not understand how the algorithmic profiling works, and underestimate its huge potential for bias. When invasive checks happen because a computer says so, by people who don't understand the system, harm is inevitable.

Risk scores decide how much evidence you have to provide to the council to get your benefits. The higher the risk score, the more invasive the evidence.

Low risk scores means officials might only ask to see copies of documents, while higher risk scores will see the council demand originals and could even lead to follow-up calls and home visits.

UNIVERSAL CREDIT MACHINE LEARNING MODELS

Universal Credit is designed as a “digital-first” benefit, with applications and communications mostly happening online. From day one the DWP has sought to make use of any data collected, including to “detect, correct and root out fraud”.

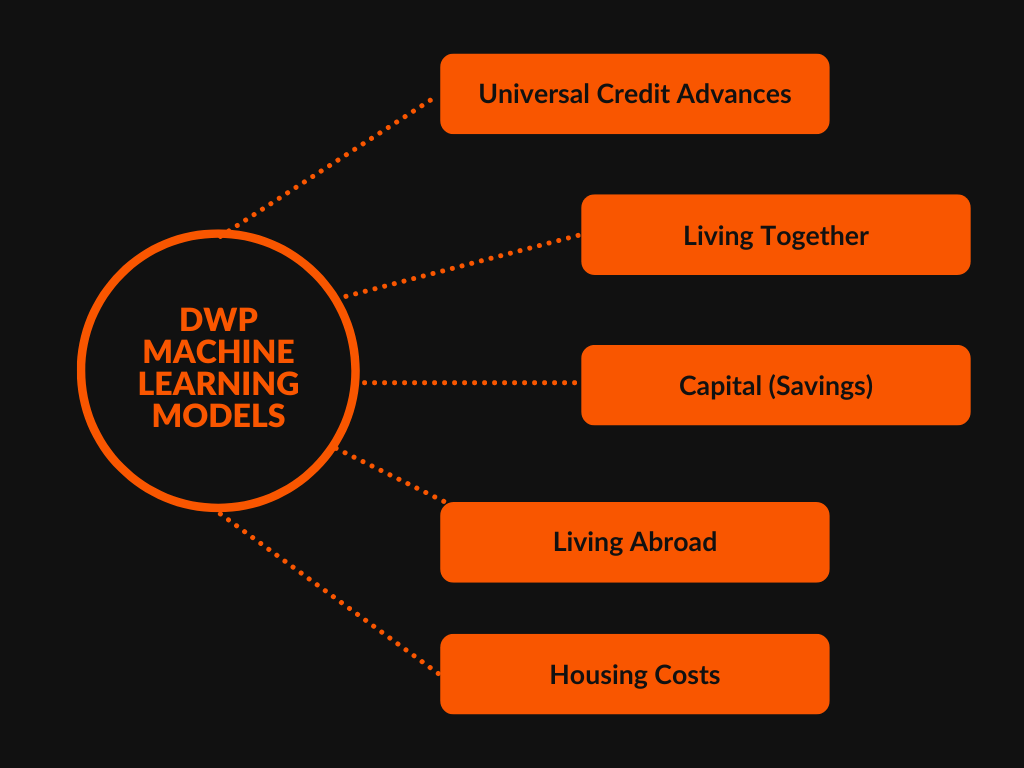

Now the DWP has developed AI models to profile the hundreds of thousands of people applying for Universal Credit each year.

The first model scanned for fraud risk in claims for advances – loans made to support people while the wheels of the welfare system turned slowly - before more were introduced.

The DWP has rolled out machine learning-powered models to profile claims for their risk of fraud for breaching capital limits, spending too long abroad, incorrect housing costs or false claims about living together.

The DWP refuses to be transparent about the data used to profile people, where this data comes from, and what happens once people have been risk-scored.

We took the DWP to court to try to force more transparency.

Although they handed over more information during the hearing, it is unclear if people flagged by the secretive algorithm even knew that the machine picked them.

Intrusive checks with zero explanation.

Demands for further documents and extra checks might come with zero explanation because the computer decides you are suspicious.

The flags might be unfair, too.

In 2023, the National Audit Office found that pre-launch bias tests were “inconclusive”.

In 2024, the DWP Annual report said there were no “immediate concerns of discrimination” but refused to publish its fairness analysis – hiding behind claims of undermining the model.

Flagged for review

Once the machine flags you, your case is sent to a DWP officer who decides what happens next.

The decision-making process is kept secret.

You might get asked for more information about your claim, have details double-checked or be subject to additional scrutiny – all while never knowing why.

HOUSING BENEFIT ACCURACY AWARD INITIATIVE

Every year, each of the more than two million people who receive housing benefit from their local councils is profiled by the DWP’s suspicion algorithms.

As part of the Housing Benefit Accuracy Award Initiative, an algorithm risk scores housing benefit claimants to predict how likely it is that their payments are wrong.

According to the DWP algorithm, the 400,000 “highest risk” cases are flagged to their local authorities. Councils are then required to conduct a Full Case Review of their claim in exchange for central government funding. Since 2022, councils have been mandated to take part in the initiative.

It is not clear what weight is given to the different factors taken into account by the algorithm.

If your score is one of the 400,000 highest – roughly in the top 6th - your name is flagged to your local council for a Full Case Review.

Councils have very limited discretion on who to review. They can usually only skip you if you’ve been reviewed recently, so for most people, an algorithmic flag means a review.

If the algorithm flags you for a Full Case Review, your local council will send you a letter demanding that you submit a lot of documents - usually within one month.

If you get all the documents to the council in time, they will scrutinise them closely, and reassess your Housing Benefit payment, depending on your circumstances.

For some claims with a big gap between what is claimed and the reality, it could lead to a fraud investigation.

If you don’t respond to the letter and get the documents together in the limited timeframe, you face your Housing Benefit being suspended first and later cancelled altogether. Letters are sent via the unreliable postal system, and could arrive late.

Thousands of people have seen their benefits suspended or terminated because they did not respond to a review in time—a review potentially triggered with little human input.

Despite using protected characteristics in its modelling, age and gender, the DWP does not think that the HBAAI could disproportionately impact certain groups.

Data obtained via FOI from the councils with the biggest Housing Benefit cohorts in the country suggests otherwise - with working-age men bearing the brunt of the reviews. It could be that those groups pose highest risk, but the DWP’s failure to consider potential disproportionality increases the chance of biased impacts.

The DWP also overstated the algorithm’s hit rate to justify the mass rollout.

A pilot found that 68% of high-risk claims involved benefit overpayment, but real-world data has found that only 34% of Full Case Reviews lead to a change in payment.

Almost 380,000 people receiving the right benefit amount have been flagged by the digital suspicion machine over 3 years, due to the DWP’s arbitrary threshold. This means the computer triggered 200,000 more reviews of people getting the right amount than was expected. The impact? Thousands of families across the country were put through high-stress reviews because the computer said so.

FIGHTING BACK

Limited transparency around Risk-Based Verification and the Housing Benefit Accuracy Award Initiative represents a sad high water mark. The DWP treats its new higher-tech algorithms as akin to state secrets.

These are just three profiling tools used in the UK welfare system - but they are not the only ones.

Court action was required to force the DWP to disclose crucial information about the data risks from its Universal Credit machine learning tools. The department initially refused to publish a single line of the Data Protection Impact Assessment in response to a FOI request. After the Information Commissioner intervened it turned over a heavily redacted copy, but we wanted more detail. In the middle of the tribunal hearing where Big Brother Watch was demanding more information, the DWP u-turned, disclosing some more of the redacted information. Secrecy is the default in the DWP - but it can be challenged.

Shadowy profiling of some of the most vulnerable people in society has the potential to cause serious harm. Coupled with a lack of transparency, it could be devastating. If welfare recipients and their advocates are left in the dark about high-risk profiling, how can anyone be expected to challenge the machine and hold it to account?

AI, algorithms and automation are here to stay at the heart of the welfare state.

The DWP argues that AI, algorithms and large-scale data analysis are needed to combat fraud in the welfare system. Sunlight, not secrecy, is needed to see into the black box and protect those in need. Mass data processing can have upsides, but it can lead to harm, error and bias on an industrial scale.